īoth encoding failures and decay account for more permanent forms of forgetting, in which the memory trace does not exist, but forgetting may also occur when a memory exists yet we temporarily cannot access it. However, once we get the right retrieval cue (a name perhaps), the memory (faces or experiences) rushes back to us like it was there all along. At times, we will completely blank on something we’re certain we’ve learned - people we went to school with years ago for example. When the consolidation process is interrupted by the encoding of other experiences, the memory trace for the original experience does not get fully developed and thus is forgotten. Memory traces need to be consolidated, or transferred from the hippocampus to more durable representations in the cortex, in order for them to last ( McGaugh, 2000). More recently, some memory theorists have proposed that recent memory traces may be degraded or disrupted by new experiences ( Wixted, 2004). Critics argued that forgetting must be due to processes other than simply the passage of time, since disuse of a memory does not always guarantee forgetting ( McGeoch, 1932).

As you might imagine, it is hard to definitively prove that a memory has decayed as opposed to it being inaccessible for another reason. His observations and subsequent research suggested that if we do not rehearse a memory and the neural representation of that memory is not reactivated over a long period of time, the memory representation may disappear entirely or fade to the point where it can no longer be accessed. He found that his memories diminished as time passed, with the most forgetting happening early on after learning. Ebbinghaus created more than 2,000 nonsense syllables, such as dax, bap, and rif, and studied his own memory for them, learning as many as 420 lists of 16 nonsense syllables for one experiment. It has been known since the pioneering work of Hermann Ebbinghaus ( 1885/1913) that as time passes, memories get harder to recall.

Most of the time this is not problematic, but in certain situations, such as when you are studying for an exam, failures to encode due to distraction can have serious repercussions.Īnother proposed reason why we forget is that memories fade, or decay, over time. Similarly, it has been well documented that distraction during learning impairs later memory (e.g., Craik, Govoni, Naveh-Benjamin, & Anderson, 1996). However, few of us have studied the features of a penny in great detail, and since we have not attended to those details, we fail to recognize them later. For example, people have a lot of trouble recognizing an actual penny out of a set of drawings of very similar pennies, or lures, even though most of us have had a lifetime of experience handling pennies ( Nickerson & Adams, 1979). Usually, encoding failures occur because we are distracted or are not paying attention to specific details. If you fail to encode information into memory, you are not going to remember it later on. One very common and obvious reason why you cannot remember a piece of information is because you did not learn it in the first place. But as we explore this module, you’ll learn that forgetting is important and necessary for everyday functionality. Why do we forget? And is forgetting always a bad thing? Forgetting can often be obnoxious or even embarrassing. Clearly, forgetting seems to be a natural part of life. Oftentimes, the bit of information we are searching for comes back to us, but sometimes it does not. Maybe you forgot to call your aunt on her birthday or you routinely forget where you put your cell phone.

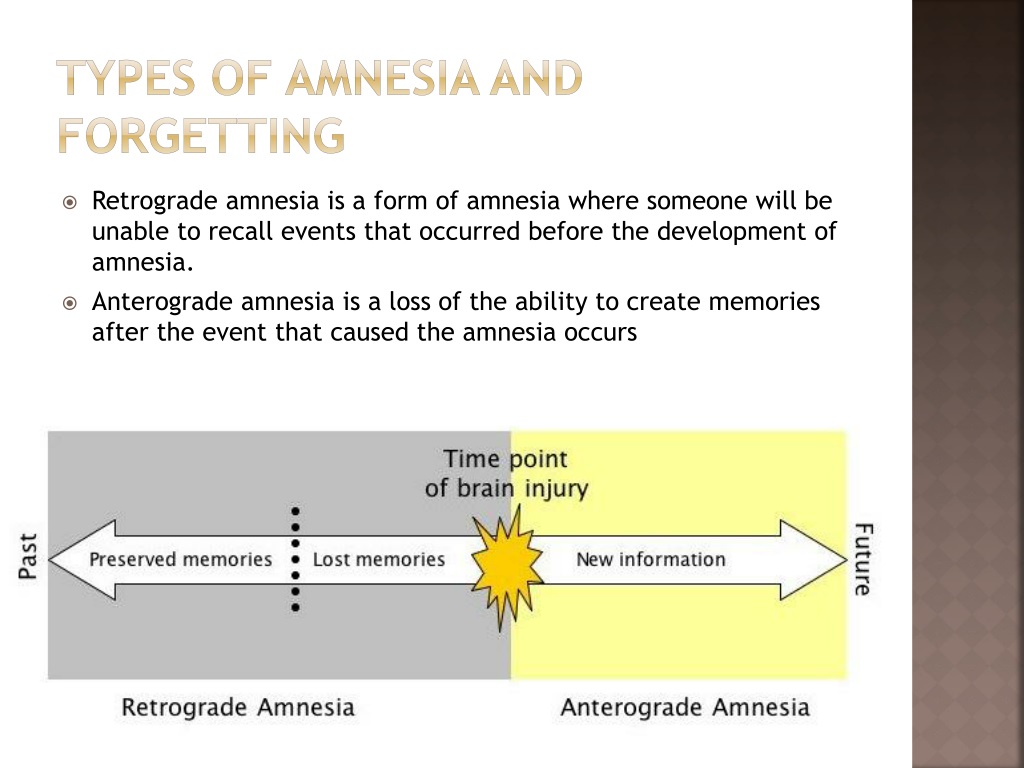

BOTH TYPES OF AMNESIA TV

You may have had trouble remembering the definition of a key term on an exam or found yourself unable to recall the name of an actor from one of your favorite TV shows.

Describe how forgetting can be viewed as an adaptive process.Identify five reasons we forget and give examples of each.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)